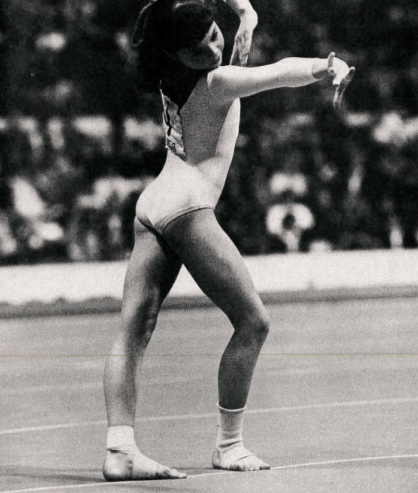

The 1981-1984 Olympic quad was filled with big names. But there were also a number of gymnasts from this quad who never received the recognition they deserved. One of those gymnasts was Soviet gymnast Olga Bicherova. The best known Soviet gymnasts of this quad were Natalia Yurchenko and Olga Mostepanova. In the four major gymnastics competitions Bicherova won more individual medals (9) than both Mostepanova (3) and Yurchenko (5) won combined.

Bicherova not only won more medals, she was the All-Around winner at the 1981 World Championships, the 1982 World Cup, and the 1983 European Championships. Only two other gymnasts (Ludmilla Turischeva and Elena Shushunova) won all three of those titles. It was Nadia Comaneci who made history by being the first gymnast to score a Perfect 10 at the Olympics. But gymnasts had a harder time breaking the Perfect 10 barrier at the World Championship level. Both the 1978 and 1979 World Championships failed to see any gymnasts score Perfect 10s despite featuring Nadia and Nellie Kim. It would be Olga Bicherova at the 1981 World Championships who would finally be the first to score a Perfect 10 at the World Championship level.

Bicherova has a resume that is just as impressive as any gymnast of that 1981-1984 Olympic quad. She would even outlast almost every one of her initial rivals by making it all the way to 1988 while still competing in major televised gymnastics competitions. And it is what she did immediately after retiring in 1988 where Bicherova’s story in retirement becomes equally as compelling as what she did as an athlete.

The Soviet Union routinely strived for milestones that allowed it to celebrate its gender equality. But what often happened is these milestones were mere symbolic appearances rather than a genuine attempt at opening up positions for women. The textbook example of this occurred during the Space Race. The Soviets sent the first woman into space with a cosmonaut by the name of Valentina Tereshkova all the way back in 1963. It wouldn’t be until 1983 that the Americans sent a woman of their own into space with an Astronaut by the name of Sally Ride.

On paper it looked as if the Soviets were 20 years ahead of the Americans when it came to gender equality in space. But there was a difference. Valentina Tereshkova became the first woman in space, but the Soviets wouldn’t send another woman into space until 19 years later in 1982 when Svetlana Savitskaya became the second Soviet woman in space. In 2014 Elena Serova became only the fourth woman in the entirety of Russian/Soviet history to venture into space. Russia hosted the 2014 Olympics and used Tereshkova, Savitskaya, and Serova as flag bearers in the opening ceremony. Russia had done everything it could to give the appearance that women were strongly represented in its space program. But what they hadn’t done is made women in spaceflight a regular occurrence.

When Sally Ride became the first American woman in space in 1983 she wasn’t a token symbol, she was proof that things were changing. Sally Ride returned to space the following year in 1984 along with three more women. Two years later in 1985 the tally of American women who had gone to space had risen to eight. The Soviets simply wanted the prestige of having the first woman in space. They didn’t want the actual change of expanding opportunities for women that came with it.

The Soviet Olympic program was more or less the same way. In 1972 Olga Korbut won over Western viewers with her dazzling performances. The 1972 Soviet Olympic team was 24.5% female. Their American rivals were only 21% female. The Soviets always seemed to have a slight edge in number of female athletes. The Soviets wanted to dominate the medal count and they realized a medal was a medal regardless of whether it was won by a woman or a man.

Women were strongly represented on the Olympic team because the gender of the athlete mattered if the Soviets wanted to win medals. But the gender of the coach didn’t. Initially women in coaching roles were protected in gymnastics for two reasons. The first was that existing rules barred men from a number of areas in the competition hall and women were required in several supporting roles to accommodate these gender rules. The second reason was that men’s gymnastics was considered more prestigious than women’s gymnastics. As a result men weren’t as interested in the top coaching spots on the women’s side.

But in the 1970s things were starting to change. The women’s rights movement wasn’t just expanding access for women. It was also tearing down archaic rules requiring gender separation. This had the unintended consequence of decreasing coaching/administrative opportunities for women in gymnastics as certain roles that were once available to exclusively women were now available to men as well. It became easier to replace a woman with a man. But this wasn’t the only example where progress had a backfire effect.

Olga Korbut’s 1972 routines were a boom for women in sport and gymnastics. Her success and fame encouraged more girls to enter sports. It had increased awareness and funding for women’s gymnastics. It also elevated women’s gymnastics above men’s gymnastics. Suddenly men became more interested in holding positions of power on the women’s side of the sport. Now they suddenly wanted the highest ranking coaching positions for themselves. And even when women managed to retain the top positions, they often struggled with male subordinates who were unwilling to accept that their superior was a woman.

Things reached a breaking point in 1976. The 1976 Soviet women’s gymnastics team was the most contentious team selection of all time. Top Soviet coach Larissa Latynina was the most decorated Olympian in not just gymnastics, but among all Olympic sports. A record she would hold for 48 years until it was broken by Michael Phelps. Against the wishes of virtually everyone, Latynina opted to keep a trio of 14 year olds (Maria Filatova, Natalia Shaposhnikova, and Elena Davydova) off the Olympic team. It was only at the last possible moment before the Olympics were to start that Filatova was elevated to a full team member taking the place of Lidia Gorbik.

Latynina was resisting innovation as the success of Nadia Comaneci had proved that young gymnasts were the future of the sport. But Latynina was correct and the veteran-laced team that she selected would go on to be statistically one of the best gymnastics teams of all time. But that didn’t matter. Nadia had dominated the 1976 Olympics and the young Romanian was the only excuse needed to get rid of Latynina. It didn’t seem to occur to anyone that finding a gymnast better than Nadia in 1976 was impossible and Latynina had effectively been given an unattainable performance requirement to reach if she hoped to retain her position. Latynina was fired. Her position up until that point in time had typically been held by a woman. It would be held by a succession of male coaches for the remainder of Soviet history.

In 1978 Victor Khomutov (coach of 1972 Olympian Antonina Koshel and Lidia Gorbik) wrote for the official magazine of the Australian Gymnastics Federation. In his report which was intended to demonstrate gymnastics tactics of the USSR that the Australians could learn from, his very first example on policies that were adopted by the Soviets that the Australians could use was in regards to the prevalence of men in the Soviet coaching ranks. He would proceed to list five reasons as to why the high ranking positions went to men:

A) Women’s work is now very complicated and requires the technique and understanding of men’s work.

B) Spotting is physically difficult, and requires the strength of a man.

C) Girls in the teen years, relate better to a man and work harder.

D) Men have no other say in Women’s Gymnastics, due to F.I.G rulings.

E) In all the top countries, the top coaches are men.

Khomutov’s writings demonstrate how prevalent sexist attitudes and arguments against women being suitable coaches had become. These were attitudes that could not only be put in writing, but were deemed acceptable enough to be endorsed by the federation of a Western program.

In another incident in 1986 Soviet coaches wrote a letter lamenting Lyubov Miromanova. They resented her being allowed to have influence in team selections and the letter goes as far as to call her pupil Svetlana Boginskaya a “mediocre gymnast” in an attempt to discredit Miromanova’s coaching ability.

Female coaches spent the 1970s and 1980s often fighting just to maintain their ranks rather than prospering. And of the gymnasts who were coached by women, the coaches often were those who had established themselves prior to the rise of Olga Korbut and/or were the spouse of a reputable male coach. On the men’s side of the sport things were even worse as there were no notable female coaches at all. At least until Olga Bicherova came along.

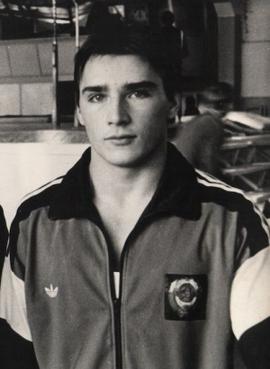

Like many of her teammates, Bicherova married young (often around their 20th birthdays) and married a notable gymnast. His name was Valentin Mogilny. The same year Bicherova retired Mogilny was named to the Olympic team. When Bicherova went to watch her husband compete on television at the Olympics, to her dismay he wasn’t there. Mogilny arrived at the Olympics as a lock for the final lineup only to be unexpectedly booted from the team. He had suffered the same fate as Lidia Gorbik had in 1976.

Mogilny returned from the Olympics as damaged goods with his reputation shattered. He had fallen out of favor with the top coaching brass and no one was willing to coach him. With her husband struggling Olga Bicherova as a loving wife was willing to do anything to help him. And that involved doing the unthinkable. She would become his coach.

Olga Bicherova is credited with being the first woman to coach men’s gymnastics at the Soviet (and later Russian) Olympic training center at Round Lake. Hostility to a female presence at Round Lake had traditionally been so extreme that women weren’t even allowed to enter the men’s training hall. The only other woman present was a masseuse named Vera and she was only allowed to stand in the doorway.

Bicherova walked right past the doorway and into the training hall. No one was willing to challenge Bicherova’s presence. Given that she had won three major All-Around titles, her gymnastics credentials couldn’t be disputed. But Bicherova didn’t have it easy either. Her fellow coaches tolerated her presence, but they didn’t accept her as an equal. Her fellow coaches did everything they could to pretend she wasn’t there. They refused to stand next to Bicherova, wouldn’t speak to her, and even tried their best to avoid eye contact. Mogilny being coached by his wife was openly laughed at and the idea of a woman thinking she was cut to be a men’s coach was equally humorous to his teammates.

But Bicherova held her ground. It must be remembered that Bicherova is of incredibly small statue. When Bicherova won her first title in 1981 American television commentators listed her as 4’ 6” and 65 pounds and would go as far as to claim she was likely only 10 or 11 years old. Unlike many of her contemporaries in women’s gymnastics, Bicherova never experienced a major growth spurt during her career. Her small appearance continued into adulthood. In reunion photos Bicherova is typically the smallest person present. Meanwhile men’s gymnastics has its origins in military training. It is a sport designed around developing a muscular body and achieving peek physical condition.

The contrast in physical presence between Bicherova as a young adult woman just entering her 20s going against elite level men’s gymnasts and their coaches who were twice her age is staggering to think about. All while being severely outnumbered in the process. It can only be imagined just how intimidating and difficult such an environment was for Bicherova. It took incredible bravery, grit and self-confidence to succeed in an environment like that.

And Bicherova would succeed. She successfully salvaged Mogilny’s career. Mogilny won two gold medals at the 1989 European Championships, a silver in the All-Around and a bronze on the pommel horse. Then at the 1989 World Championships he became a World Champion on the pommel horse and won a silver in the All-Around. The following year he would win three gold medals at the European Championships including the All-Around title. Bicherova coached Mogilny to ten medals and eventually everyone at Round Lake had to concede that Olga knew what she was doing.

It was especially difficult for Bicherova and Mogilny to maintain a coach and pupil relationship while also being husband and wife. Like many of her teammates, Bicherova grew up in an environment where the husband was viewed as the head of the household and women found self-fulfillment in meeting the wishes and needs of their spouse. But in an elite level coaching relationship it is the coach who is the dominant voice in the partnership. Bicherova would later go on to say Valentin was the boss at home and she was the boss in the gym.

Mogilny failed to make the 1992 Olympic team and would suffer a series of health issues. He died at the age of 49. The couple only had one child, a son by the name of Alexey. Bicherova is happily remarried and would give birth to two more children.

I am fascinated by the level of research in this article. Thank you for this. I am definitely following this.

LikeLike

I am not. The author just had strong urge to show his/her gender opinion on things he/she doesn´t understand. Ask Olga what she thinks of your article!

LikeLike

Me fascinó el articulo. Si antes admiraba a Olga, después de conocer su historia como entrenadora, la admiro más.

LikeLike