Link: to Part I of this article

Elena Mukhina is largely remembered for two things. The first was beating Nadia Comaneci to win the 1978 All-Around title which marked her rise to the very top of the gymnastics world, but also her unfortunate demise. Mukhina’s career ended in tragedy, an injury on the eve of the 1980 Olympics left her paralyzed from the neck down just one month after celebrating her 20th birthday. It would ultimately result in her premature death at the age of 46.

These events overshadow what were two other hallmarks of Mukhina’s career. The extreme political dynamics of the era that Mukhina’s athletic career were defined by, and her rapidly rising up the ranks so fast, that it should have been impossible. For Mukhina, just making it to the elite level was a staggering athletic accomplishment in itself.

When Olympians take a year off, they typically resume high level training with two years to spare until the next Olympics because that’s how long it takes to relearn their old skills, perfect Olympic-level routines, condition their body, and acquire muscle memory. That’s just how long it takes for returning Olympic gymnasts. Mukhina spent 18 months to go from having never done high level routines to being capable of holding her own against your average Olympian.

I’d estimate that most gymnasts would have needed about 5-8 years to go from where Mukhina was in 1974 to her emergence as a possible contender for the 1976 Soviet Olympic team. Every single factor dictated that a gymnast needed time to rise that fast. Besides the previously mentioned obstacles such as conditioning and learning new skills, gymnastics is a reputation based sport, “first you work for your name and then your name works for you.”

Mukhina defined that classic proverb because she was just that good. In a sport where reputation, experience, and youth were three critical assets, Mukhina was beating gymnasts who were younger than her, had twice as much experience including being veteran Olympians, and were once well known child prodigies. It didn’t make sense that Mukhina would be the one who would prevail, and it certainly didn’t make sense that this is how it would be in 1977 and 1978.

In 1976 Nadia Comaneci dominated the Olympics when she was only 14 years old. The Olympics were barely over before the media had already started to wonder if Nadia would be usurped in 1980 in the same way Korbut had been usurped in 1976. What the media had envisioned was a clone of Nadia Comaneci, a hypothetical gymnast who would be 14 years old in 1980, but was only 10 years old in 1976. Whereas everyone was thinking that the next great breakout star was going to be a junior between the ages of 10-12, it ended up being a 17 year old Elena Mukhina. Adding to the perplexing chain of events making Mukhina was the most unlikely gymnast to have ever achieved breakout success.

Mukhina’s breakout success while being older than most of her competitors is one of WAG’s greatest anomalies. It occurred alongside contemporary examples such Olga Mostepanova, the top Soviet gymnast of 1984 who first competed against Olympians, in a British competition that was being broadcasted on television when she was only ten years old. Mostepanova’s Romanian rival Ecaterina Szabo had a similar story. She was discovered by Bela Karolyi in 1973, was featured in an American television program in 1976, and had been sent to the Olympics as an observer in 1980, all before making her 1984 Olympic debut at the age of 16.

The unlikely gymnast and the unlikely coach is an important component to Mukhina’s story because the combination of an unconventional gymnast joining forces with an unconventional coach was a key reason for their shared success. The duo fit each other like a hand entering a glove and had success that would have been impossible under any other circumstance. But it also made their relationships mutually self-destructive.

By her own admission, Mukhina called herself a “coward” and was determined to break that label. She was going to say “yes” to anything and wasn’t willing to question the limits. Mikhail Klimenko was a relatively young coach who was trying to prove himself, and was far too willing to push the limits and win by any means necessary. It was the worst possible combination, a gymnast willing to tolerate anything her coach threw at her, and a coach willing to push a gymnast as far as he could.

I do not believe it was a coincidence that this story ended in tragedy, but the tragic ending was a direct byproduct of the unconventional backgrounds Mikhail Klimenko and Elena Mukhina shared. Mikhail Klimenko was a first-time WAG coach trying to prove himself in a Soviet WAG program that had been defined by celebrity-WAG coaches throughout the 1960s and 1970s. Klimenko was trying to establish himself as one of their equals and I cite that as a factor as to why he pushed Mukhina beyond the limits.

The celebrity coaches Mikhail Klimenko was competing against often had dozens of young, aspiring gymnasts. If their top Olympic prospect was injured, they had other Olympic prospects to work on. If not in time for 1980, then certainly those who were on a track for 1984. For Mikhail Klimenko, Elena Mukhina was his best shot at becoming an Olympic coach and in 1979 there didn’t appear to be anyone else with similar potential in his training group.

Lastly, Mikhail Klimenko pivoted to WAG only after his coaching career in MAG had failed to materialize. Now his WAG coaching career was experiencing a rut as Mukhina entered a decline in 1979. It should be questioned how much Klimenko was being motived by his own personal goal of overcoming career failure.

I don’t exactly sympathize with Klimenko, but I do see him as a tragic villain. For a wide variety of reasons, he had become overly invested in a single gymnast. As an athlete, his Olympic dream was stolen from him and he was living that dream though his own pupil. As a human being, he was trying to escape the shadow of his brother and establish a name of his own. As a person, he wasn’t just trying to preserve his coaching career, but his social status in which his coaching career depended on. All of that rested on the performance of a single individual, Elena Mukhina. For Mikhail Klimenko, Mukhina was too important to his career for her to fail.

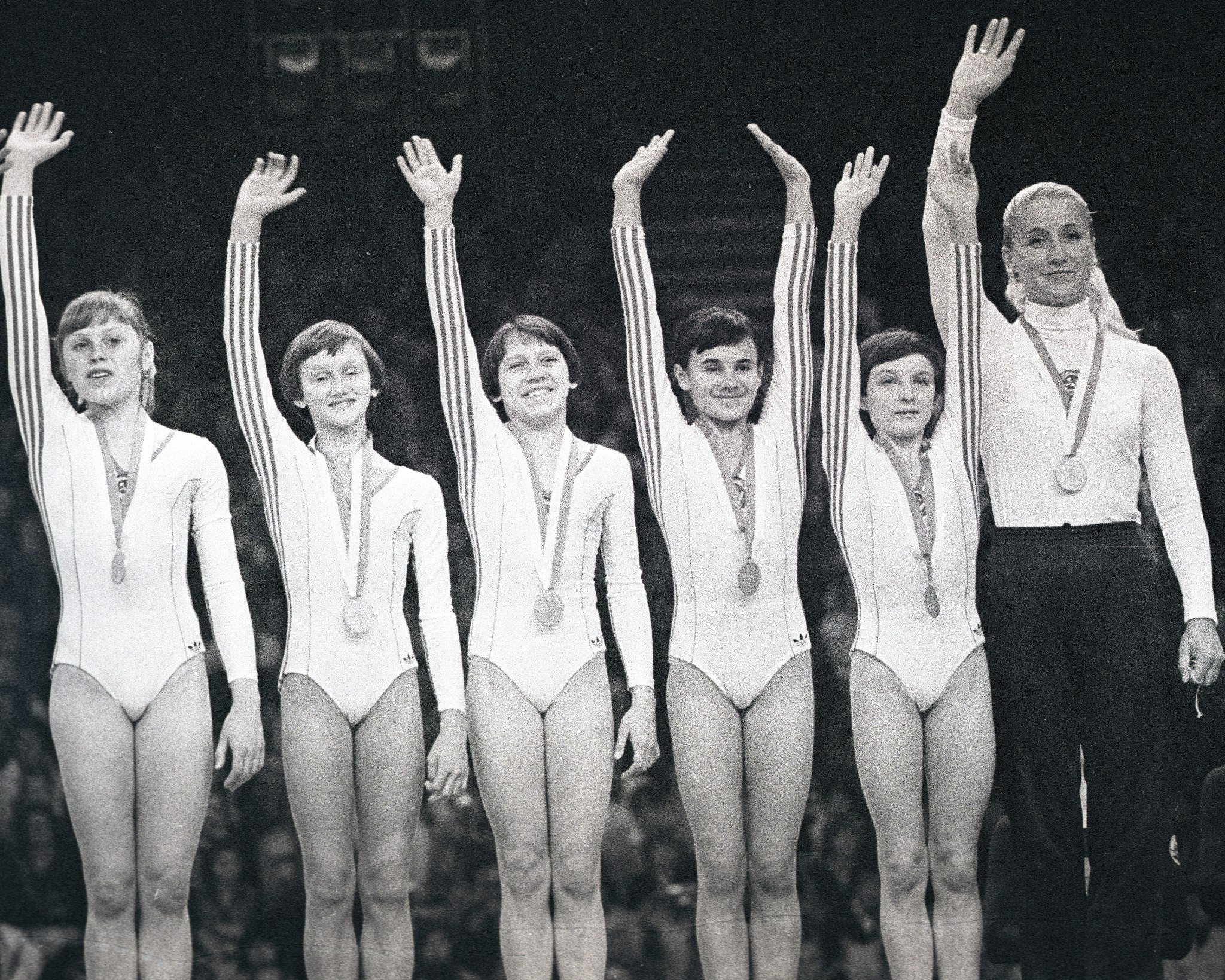

Mikhail Klimenko’s treatment of Mukhina was atrocious, and there is so much to say on that topic that it deserves its own separate article. Stella Zakharova compared him to infamous Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet and called Klimenko a “tyrant.” Maria Filatova referred to Klimenko as “a beast” and when given the option to be coached by him said, “I wouldn’t go to Klimenko even at gunpoint.” Both were members of the 1980 Soviet Olympic team and had trained alongside Mukhina. Mikhail Klimenko deserves significant blame for Mukhina’s injury, but there is one particular detail that is frequently overlooked.

Mikhail Klimenko was in a different city when Elena Mukhina was injured.

The tragedy of Mikhail Klimenko is that it was he who carried most of the blame. Even though Mukhina herself would later state her injury was not the byproduct of a lone individual, but the flawed Soviet system as a whole. Mukhina went as far as to say she felt sorry for Klimenko and classified him as “a victim of the system.”

After analyzing all the information available, I believe Mukhina is completely correct to pin a majority of the blame on the Soviet WAG program as a whole. The day Mukhina was injured, Soviet national team coaches working with her had violated half a dozen safety guidelines. The people responsible for following those guidelines were the ones in the room at the time of the accident, not the coach 440 miles away.

The very same Soviet officials who blamed Mikhail Klimenko for his horrible treatment of Elena Mukhina as being a factor which lead to her injury, were the same Soviet officials who knew about his behavior for years prior. They hadn’t just tolerated Klimenko’s practices, but had become so satisfied with his results that other high profile Soviet gymnasts had been encouraged to switch gyms and join his training group.

At the time, Soviet officials were being pressured to build a team which was superior to that of the Romanians. They were being pressured to make sure the Moscow Olympics featured the strongest lineup of Soviet gymnasts to ever be assembled. In the context of larger geopolitical events, Soviet leadership wanted results and were willing to push the limits. They ended up getting more than they bargained for, and the price for that was paid by Elena Mukhina.

None of this is to say I completely absolve Klimenko of blame, as I do consider his coaching tactics to be a significant factor leading to Mukhina’s paralysis and even agree with Soviet officials on that particular point. Where I disagree with Soviet officials is their claim that it was all Klimenko’s fault.

Under Klimenko, Mukhina’s injury history had been so atrocious that her paralysis was the inevitable result of what happens when a gymnast is taught over and over again that reckless behavior is the only way forward. Klimenko had delivered a broken gymnast to the Soviet team, and it was he who deserves the blame for breaking her. Klimenko had broken Mukhina mentally, and he had also broken her physically. But it was the coaches of the Soviet national team who had been the ones who ultimately destroyed Mukhina in a way in which she could never recover.

Mikhail Klimenko maintained a viable coaching career in the aftermath of Mukhina’s injury. Most notably Aleftina Pryakhina who won two medals at the 1987 European Championships, exactly ten years after Mukhina achieved breakout success at this very same competition in 1977. It was enough to declare Mikhail Klimenko a coach with “repeat success” and from that point forward, he could never be dismissed as an untalented coach who had simply gotten lucky with Mukhina.

But the more time passed, the more Klimenko’s career seemed to regress, at least in international competition. It is hard to say if the memory of Elena Mukhina stifled Mikhail Klimenko’s career, but it did appear to be more of a limitation for him than other coaches who had associations with infamous injuries such as Al Fong. Elena Mukhina passed away in 2006, 11 months later Mikhail Klimenko passed away at the age of 65. Whether lingering guilt and depression were contributing factors to his death is an answer we will never know.

This article isn’t an attempt at rehabilitating Mikhail Klimenko or trying to paint him in a more sympathetic light. But rather, it is about celebrating Elena Mukhina. She does not get enough credit for how rapid and unexpected her rise was. It culminated in achieving the top ranking in the sport and having one of the most dominant All-Around performances in WAG history. It wasn’t until Simone Biles that WAG had another gymnast who rapidly appeared from out of nowhere in the same fashion as Mukhina.

I think back to that snowy day in late December of 1974 where a coach and a gymnast crossed paths for the first time. On their own, neither seemed capable of accomplishing the goals they so desperately wanted to achieve. Together, they accomplished more than they could ever dream and reached levels they once considered to be impossible. But for both of their sakes, it would have been better if they never met at all.

Link: to Part I of this article

A great history and analysis… a tragic result… with a winning at all costs attitude, only disaster results… always… look at the US program under Karolyi.. the success masked the tragic and sinful culture… there will always be the next champion… but certain things can never be erased.. and should not be forgotten !

LikeLike

Hi, slightly off topic but there is a film called “Something different” by Vera Chytilová that features Eva Bosáková, a Czech gymnast of the 1950’s and early 60’s. You can find it on BFI player if you are interested. I thought you would like it given your interests in WAG history.

LikeLike

Todavía no entiendo por que no han hecho una película de esta extraordinaria atleta. Nació con talento. Logró en tampoco tiempo lo que otras lo hicieron en más años.

El título que le pondría a esa pelicula sería:

“MÁS ALLÁ DE SUS LÍMITES” porque eso fue lo que Klimenco con Mukhina.

Ella debe estar en el salón de la fama

Internacional. JUSTICIA!!!

LikeLike

This article is not professional at all and is based on the dissemination of false and defamatory information.It was a tragedy in the lives of both protagonists.

Hostile people wanted to exploit the case to defame Mikhail Klimenko. I am extremely surprised especially how you can make articles without verifying the veracity of the information.

Those who know the reality of the facts have never accused Mikhail Klimenko

When the tragedy happened, he wasn’t even present and had given instructions not to perform any combination. So I find it reluctant to say that it led to performance beyond all limits.

any legal action will be taken accordingly

LikeLike