Throughout history there were numerous examples of an entire generation of Soviet gymnasts getting the short end of the stick. Gymnasts who were “victims of circumstance” who through no fault of their own, had their Olympic prospects derailed. The best known example of this were the gymnasts impacted by the 1984 boycott. There were also Soviet gymnasts who missed out on the Olympics because they competed prior to 1952 when the USSR hadn’t yet joined the Olympic movement.

And then there is a generation of Soviet gymnasts who I nickname the “1940ers” because they were all born in the 1940s and were at the height of their careers from 1962-1970. This was a generation of Soviet gymnasts that fared poorly when it came to earning major international assignments. Whereas the Soviets of the 1984 boycott and the Soviets prior to the 1950s were denied their opportunity to compete in the Olympics because Soviet gymnastics was denied the ability to send any team at all, the Soviets of the 1962-1970 era were different.

This was a generation of Soviet gymnasts who were discarded to the benefit of the gymnasts who came both before and after them. In the end, this group of gymnasts paid the price so that other eras of Soviet WAG could prosper. If you were a Soviet gymnast, you simply did not want to be born in the 1940s.

Soviet gymnasts born in the 1940s accounted for just 6 appearances at the Olympics. In contrast, gymnasts born in the 1930s accounted for 15 appearances while gymnasts born in the 1950s accounted for 14 appearances. There are five Soviet gymnasts born in the 1930s who went to multiple Olympics. There are also five Soviet gymnasts born in the 1950s who went to multiple Olympics. But the number of Soviet gymnasts from the 1940s who can say the same?

Zero

Call them the “unlucky generation” or call them the “lost generation,” but an entire decade worth of gymnasts found themselves sidelined in ways they shouldn’t have. There were seven gymnasts from this generation who competed in a World Championships and/or Olympics who were born in the 1940s.

Irina Pervushina

Ludmilla Gromova

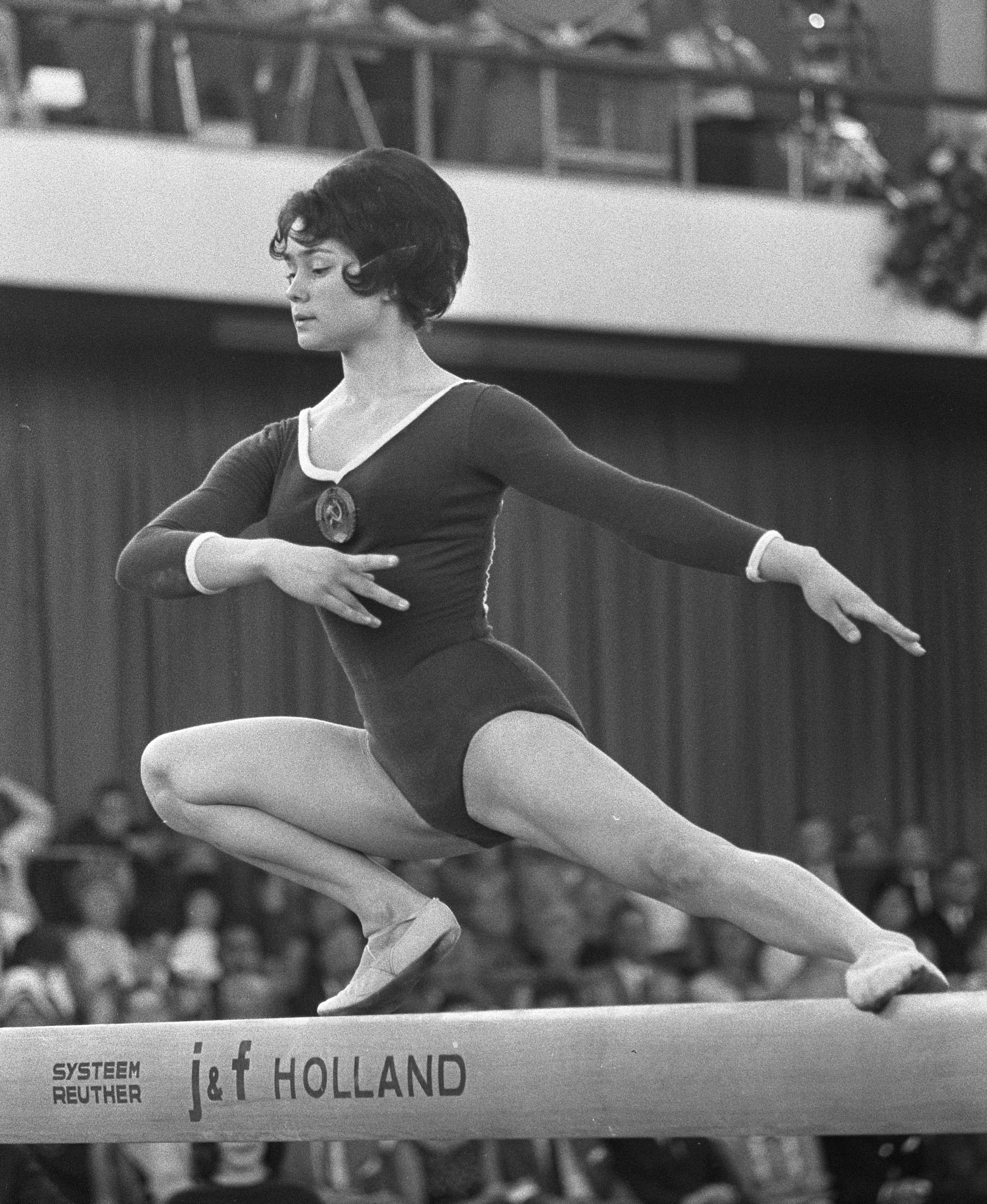

Elena Volchetskaya

Zinaida Voronina

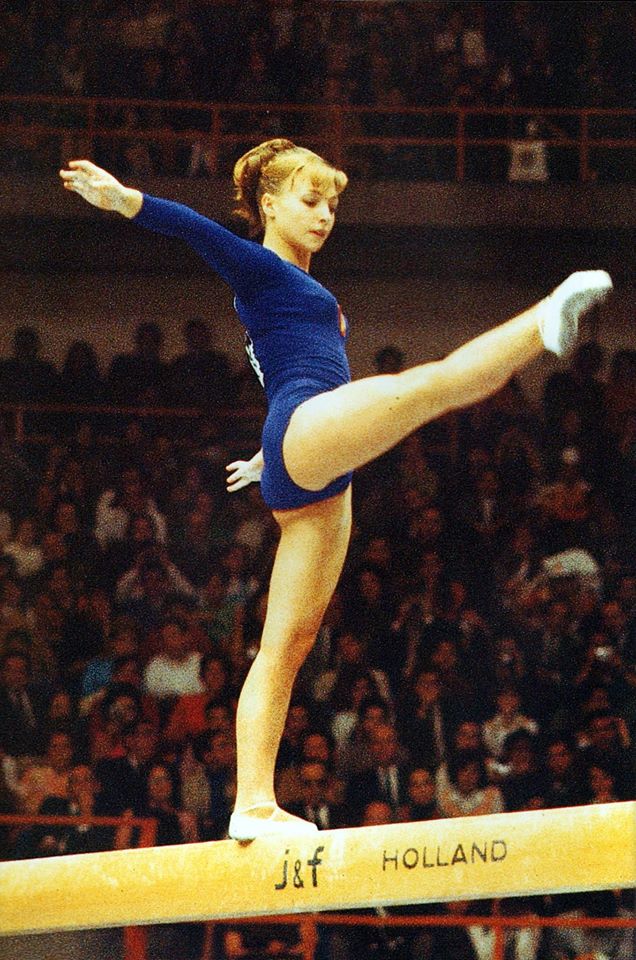

Natalia Kuchinskaya

Larissa Petrik

Olga Karaseva

What makes the plight of the 1940ers so unfair is the fact that none of them were allowed that highly prestigious second Olympic appearance. While gymnasts who operated very close to their era were afforded multiple Olympic appearances with ease. Gymnasts born in 1942 (Pervushina), 1942 (Gromova), and 1944 (Volchetskaya) did not go to multiple Olympics. But gymnasts born in 1936 (Polina Astakhova), 1937 (Lidia Ivanova), and 1939 (Tamara Lyukhina) did.

On the other end of the decade the exact same scenario occurred. Voronina (1947), Kuchinskaya (1949), Petrik (1949), and Karaseva (1949) are all 1x Olympians. But Ludmilla Turischeva (1952), Elvira Saadi (1952), and Lyubov Burda (1953) each went to multiple Olympics.

The 1940ers didn’t struggle to win spots on Soviet teams because they lacked talent, quite the opposite. The 1940ers were one of the most historically significant generations in WAG history. It was the 1940ers who gave WAG its first major surge in popularity and without the foundation they laid, the careers of Olga Korbut and Nadia Comaneci wouldn’t have been possible.

Part of the reason this generation fared so poorly is because they did so much to revolutionize the sport, that they were ushered out of the starting lineup by younger gymnasts who were better suited to the new era of gymnastics the 1940ers had pioneered. In the end, the 1940ers were victims of their own success.

By now you’re probably wondering what was it about having a birth year in the 1940s that made things so difficult for a Soviet gymnast from that time period? The answer can be found in the following graphic:

For most of the Cold War, the average age of Olympic gymnasts declined. Anytime a sport experiences such a decline in two consecutive eras, it creates an “age crunch” where gymnasts are forced to retire prematurely to make room for younger gymnasts.

Imagine a 15 year old gymnast being unable to make an Olympic lineup because she’s competing in an era where gymnasts are typically between the ages of 18-27. That gymnast is forced to wait three years and finally joins the elite ranks starting at the age of 18. As long as she makes it to age 27, she will have the same 10 year career as the gymnasts who came before her.

If the average age of Olympic WAG stays the same, she will be replaced by an 18 year old, at the age of 27, after a 10 year career. But that doesn’t happen. During her career the average age of the sport drops by three years, resulting in her being replaced by a 15 year old, at the age of 25, after only a seven year career.

The inevitable result of a sport experiencing the average age of its athletes decline, the average career length declines as well. This phenomenon occurred in just about every era of Soviet WAG. Not even Maria Tyshko who was the very first Soviet gymnast to win an international competition all the way back in 1937 was immune from this trend. So if this trend impacted Soviet gymnasts from other eras, why did it disproportionately impact gymnasts born in the 1940s? The answer to that question can be found in the graphic below.

Few Soviet gymnasts ever got through their career without being impacted by an “age crunch.” But the severity of the age crunch depended on how fast the average age of the sport plummeted over the course of their career. Gymnasts born in the 1940s typically came of age in the mid-1960s and would have been at their peak during the 1968 Olympic quad. They would have found themselves in the role of aging veterans on the downside of their careers by the time the 1972 Olympics came around.

The 1968 Olympic quad experienced what was by far the largest drop in athlete age throughout the course of WAG history. It was followed by the 1972 Olympic quad which had the third most extreme rate of decline in the average age of Olympic gymnasts. For a gymnast of any nationality, this high rate of decline would have been offset to a certain extent if the same trend occurred at beginning of their careers.

Whereas the trend of declining age is to the detriment of older gymnasts, it was also to their benefit back in the early stages of their careers when they were younger. Most notably during the time frame in which they were transitioning from the junior to senior levels. Most of the 1940ers made that transition in 1964. What happened in 1964 when it was the lone time period where declining ages would have benefited the 1940ers?

The average age of the sport actually increased.

The 1940ers were ultimately hit with a “triple whammy” by having age trends in the 1964 quad go up when the 1940ers needed them to go down. Only for those very trends to go down in the 1968 and 1972 quads when the 1940ers needed them to go up.

In their youth the 1940ers were told they would have to wait their turn. They followed the rules of the time which dictated a 14 or 15 year old would be passed over in favor of a 22 or 23 year old. But when they themselves became 22 and 23 year olds the rules had changed. Suddenly it was WAG norm to pass over a 22 or 23 year old in favor of a 14 or 15 year old.

Perhaps that is one of the factors which makes this such an irking story. That a generation of gymnasts essentially waited their turn only to have their turn given to a younger generation of gymnasts who never had to wait. Or perhaps the most irking component of this story is that whereas the 1940ers were set up so poorly for success, the gymnasts born in the early 1950s had success come so easy to them.

The trio of Kuchinskaya, Petrik, and Karaseva were born in 1949 and never had a viable path towards the Olympic Games outside of 1968. Their contemporary Ludmilla Turischeva was born in 1952 and went on to compete in the Olympics in 1968, 1972, and 1976. By simply being three years younger, Turischeva became a 3x Olympian. And it wasn’t just Turischeva who benefited from this trend. In just 1952 and 1953 alone, there are more Olympic appearances from gymnasts with those two birth years than the entire decade of the 1940s.

Look no further than the 1968 Olympic team itself. Four of its members had birth years in the late 1940s. But of the two remaining members who had early 1950s birth years, they have more Olympic appearances than the rest of the team combined.

So why did any of this happen? Why did the 1968 Olympic quad have such an extreme drop in age which came to the detriment of the 1940ers? The answer can be found in the careers of the 1940ers themselves. Volchetskaya (1944) can be described as the first gymnast in all of WAG history who had a well documented junior career. I frequently describe her as WAG’s first child prodigy.

But the real breakthrough came in 1964 when a 15 year old Larissa Petrik (1949) defeated Larissa Latynina in an Olympic year at the USSR Championships. The result received international press attention and sent shockwaves throughout the sport. In response everyone started taking a closer look at the younger gymnasts in an attempt to find the next Larissa Petrik. If Elena Volchetskaya was the first to walk the path of a junior career, Larissa Petrik was the first to prove these juniors were strong enough to beat a highly renowned senior.

The ultimate reason for the downfall of the 1940ers is they proved young gymnasts could have success, and their coaches responded by replacing them with gymnasts who were even younger than themselves.

But for most of the 1940ers, they at least received a lone Olympic appearance which is more than Olga Mostepanova and Natalia Yurchenko can say. But part of the dilemma of being a member of the 1940ers is they weren’t just passed over as athletes, but the trend continued even after their athletic careers ended.

Sofia Muratova (1929) and Larissa Latynina (1934) would achieve high level roles as national coaches of the Soviet team. The same could be said for Polina Astakhova (1935). For future Soviet gymnasts it was a rite of passage to be pictured with Polina Astakhova at a major competition. Polina would famously be pictured alongside Olga Korbut, Elena Mukhina, and Elena Davydova when they were at the peak of their gymnastics success. There is also Lidia Ivanova (1937) who is arguably the most high profile television commentator for Russian language WAG broadcasts and still maintains a strong television presence to this day.

Meanwhile Ludmilla Turischeva (1952) would take on key roles in both Soviet and later Ukrainian WAG. Lyubov Burda (1953) would be a key administrator within Russian gymnastics and to this day is frequently pictured at major Russian gymnastics competitions. At the height of her career Elvira Saadi (1952) was Canada’s top performing WAG coach. And of course, Nellie Kim (1957) who is one of the most high profile administrators FIG has ever had.

The gymnasts who came shortly before and shortly after the 1940ers would be well represented at the administrative level. While the 1940ers themselves achieved only modest success in their post athletic careers.

Once again, this isn’t so much a fluke occurrence, but was a trend that was a direct byproduct of the very success the 1940ers achieved coming back to work directly against them. One of the hallmarks of the 1940er generation is that it was they who were responsible for popularizing WAG. If Larissa Petrik proved that young gymnasts were the future of the sport, it was Natalia Kuchinskaya who proved how popular a young gymnast could be with spectators.

If Olga Korbut (1955) was WAG’s first international superstar, Kuchinskaya was the first WAG to have any star power at all. Besides being the only gymnast (to this day) to win a medal on every event in her debut at the World Championships, Kuchinskaya’s success during the 1968 Olympic quad is what forced television networks to aggressively cover WAG for the 1972 Olympics. It was Olga Korbut who proved that if the television networks covered WAG, it would be a ratings hit. But that couldn’t have happened unless Kuchinskaya had first convinced television executives to set their sights on WAG heading into the 1972 Olympics.

It was as if Kuchinskaya laid a foundation of cement so that Olga Korbut could build a house right on top of it.

Voronina (1947), Petrik (1949), and Karaseva (1949) all aggressively pursed a spot on the 1972 Olympic team. When the trio came up just short, 1972 the year “Korbut mania” was at its peak would also be the year these 1940ers either retired or got demoted from the elite level of the sport. The best thing for a female athlete is to be actively competing when your sport is in the middle of an unprecedented popularity surge. The worst thing for a female athlete seeking a coaching position is to retire in the middle of such a surge.

When a women’s sport achieves widespread popularity for the first time, it actually correlates with a decline in opportunity for women in administrative roles. The reason being, as the wealth, fanbase, and importance of a female sport grows, it makes being a coach in said sport more prestigious as well. Resulting in an influx of male coaches from the men’s side transitioning to the women’s side and taking most of the key positions for themselves.

The 1940ers never obtained positions of influence in WAG that was common for gymnasts born in the 1930s. Whereas veterans of the highly successful 1972 and 1976 Olympics born in the 1950s and 1960s had the star power/name recognition to find the very post-athletic success that had been denied to the 1940ers.

The plight of the 1940ers is that first they were young athletes in an era dominated by older athletes only to become older athletes in an era dominated by youngsters. When it was their turn to pivot into coaching, television, and other influential roles, it occurred at a time when circumstances had changed and those positions weren’t as readily available as they had been to the generation of gymnasts who had retired as little as five years earlier.

For the 1940ers, nothing really went right with this generation. At every step of the way they came of age at the wrong time, whether it be as juniors, as seniors, and young adult women trying to find opportunity as a retired athlete. And it resulted in their being an overlooked generation even to this day. They became the group of gymnasts even the gymnastics establishment forgot about.

At the 1976 USSR Cup a staggering seven gymnasts who were present at this competition were later inducted into the International Gymnastics Hall of Fame. An eighth gymnast (Elena Mukhina) is expected to be inducted when the COVID-19 situation allows for another induction ceremony to be held. That’s seven (going on eight) soviet gymnasts from a single year who have achieved widespread recognition.

In contrast, the 1940ers represent an entire decade and only one gymnast from that era (Natalia Kuchinskaya) was inducted into the Hall of Fame. Ironically, it was the only member of this generation who choose to retire prematurely rather than get pushed out by a younger gymnast who ended up getting the honor of being inducted. But Natalia Kuchinskaya is one of the most obscure gymnasts in the International Gymnastics Hall of Fame, especially amongst younger fans.

To test my theory of Kuchinskaya being one of the least widely known gymnasts in the International Gymnastics Hall of Fame, I polled my Twitter followers. 47% of respondents answered they had never heard Kuchinskaya’s name before. An additional 33% stated they knew the name of the gymnast “but not much else.” This in regards to a gymnast who was the biggest name in the sport at the time of her retirement. No other gymnast suffered a larger fall from grace in regards to her popularity. The reason being, the arrival of 1970s superstars like Olga Korbut and Nadia Comaneci made people quickly forget the story of Kuchinskaya.

Erika Zuchold (born 1947) of East Germany is the most telling example of how unfair things were for the Soviet 1940ers. Zuchold competed at the 1968 and 1972 Olympics, she was also the top ranked East German of 1964 but missed the Olympics due to an Achilles’ tendon injury. Effectively making her a gymnast who easily could have become a 3x Olympian.

Zuchold and Voronina shared the same birth year. They also competed against each other at the World Championships, Olympics, and European Championships on four seperate occasions with their medal counts being virtually identical in those four years. But because Voronina was squeezed out of the Soviet program while Zuchold attended the 1972 Olympics and won additional medals for East Germany, Zuchold finished her career with the higher medal count. Zuchold was later inducted into the Hall of Fame as a result.

Despite winning four medals at the 1968 Olympics including an All-Around silver, Voronina is not in the Hall of Fame. Nor is her teammate Larissa Petrik who was the gymnast most responsible for pioneering the little girl era, she also won three Olympic medals in 1968. In contrast, Elvira Saadi and Lyubov Burda are both in the Hall of Fame and neither gymnast won an Olympic medal in an individual event.

To conclude this article, there are two things that make the 1940ers significant.

Larissa Latynina and Olga Korbut were the two Soviet gymnasts who achieved the greatest legacy for themselves. For many gymnastics fans, these are the only two Soviets they are familiar with who competed prior to the 1976 Olympics. Yet for Latynina and Korbut, they couldn’t be any more different when it came to era, age, style, and body type.

The 1940ers were the “missing generation” in between Latynina and Korbut. The group of gymnasts who led WAG out of the classical/romantic era most commonly associated with Latynina, and into an era of rapidly accelerating change which made Olga Korbut’s career possible. When it comes to acknowledging the gymnasts who had the greatest impact on the sport, the 1940ers were as important as any generation.

For the 1940ers, their 37 combined medals at the Olympics and World Championships was quite staggering given the circumstances. But their Olympic glory and accomplishments would be forgotten, their legacy wouldn’t live on though their participation in high profile television, judging, coaching, and FIG roles. Instead, their legacy would be the gymnasts who came after them.

This is the second component of the 1940ers which makes their story so significant. No other generation of gymnasts did so much to setup their younger teammates for success. It is significant to note that half of the 1972 Olympic team shared a coach with a 1940er.

2x Olympian Lyubov Burda was coached by the same man who coached Irina Pervushina who won four medals at the 1962 World Championships. Burda is most famous for her skill (Burda Twirl) on the uneven bars. Pervushina had been the World Champion on that very apparatus only five years before Burda debuted her trademark skill.

Tamara Lazakovich was not only clubmates with Larissa Petrik, but it was Petrik who first noticed a seven year old Lazakovich and convinced her coach to take the kindergartner into his training group. And then there was 1964 Olympian Elena Volchetskaya and Olga Korbut who were trained by the same coach. But before that happened it was Volchetskaya herself who was the first person to ever give Korbut serious gymnastics training.

As the next generation of gymnasts took their place in the Soviet program, they went on to dominate the Olympic scene. With three exceptions, every Soviet Olympian of the 1970s would appear in multiple Olympics. That repeat success was only possible thanks to the abnormally short careers of the gymnasts who came immediately before them.

I wouldn’t make the claim that the 1940ers can’t be measured based on the number of medals they won. At 37 combined medals, they won far too many medals for their massive medal tallies to not be considered impressive. For comparison, it is the exact same number of medals Kyla Ross, McKayla Maroney, Jordyn Wieber, Aly Raisman, Gabby Douglas, and Viktoria Komova all won combined.

The question is, if 37 medals is what the 1940ers accomplished in the short time they were given, imagine the type of legendary status they would have achieved had they been given more time…

What lovely photos! Baraksanova and Illienko 1984 were unlucky too and we were a little lucky in having the b&w vids released.

LikeLike

If Kuchinskaya had not retired, Korbut never had been in the Soviet Team in 1972, because she was the star of stars and her style was very different of Korbut. Au contraire, Petrik and Voronina were washed out by 1971. And Tourisheva career would have been very different under the shadow of Kuchinskaya.

LikeLike

Is it possible that there are also overall fewer Soviet gymnasts born in the 1940s due to the drop in birth rate during the Second World War? I noticed in the article that most of the 40s’ gymnasts you mention here were born post-45. I imagine that a lack of depth in the pool of 40s’ gymnasts would have also potentially contributed to their unluckiness. I apologize if this is something you’ve addressed in a previous article.

LikeLike

Quizás me aleje un poco del tema, pero no pude ocultar mi alegría al saber que La GRAN ELENA MUKHINA fue admitida en el Salón Internacional Fama de Gimnasia…

Aunque ella ya no esté con nosotros, sus fans nos llena de gozo que al fin se le hizo justicia.

Solo espero que escribas algún día sobre este reconocimiento de Mukhina al Salón de la Fama, así jamás será olvidada.

LikeLike